Blog

-

The community contribution so far

Vincent, the PTA Treasurer, with the bricks the that will make the school

There’s a lot of work to be done and expensive materials to be sourced, but the community of Simakakata has already invested thousands of man hours into creating their new school. An area of dense scrub land has been cleared, foundations dug and 60,000 bricks have been made, all by hand.

The bricks are made by recovering loose soil from anthills, which is placed into a rough wooden frame, mixed with water and then compacted. The mud block is then left in the sun to dry. When there are enough bricks, they’re stacked over a large fire which must be kept burning for three days to harden them off.

It sounds simple, but the time it takes to walk several kilometres to the build site and work means time away from looking after their livestock and farms, which they need to tend to survive.

The contribution doesn’t end there. Those with certified building skills have committed to taking time off work to complete the project, because the school means so much to them.

Leave a comment -

Inside the school at Simakakata

The school building at Simakakata. The borehole in front is dry.

Why does the community of Simakakata need a school?

The current school is in a near derelict farmhouse. Most of the windows are smashed and the panels of the corrugated iron roof are punched through with holes. In places the sheets simply don’t join, leaving gaps running half the length of a classroom.

The walls are cracked and crumbling, because they seep with water in the rain then dry quickly in the burning sun. Despite the fact they are so open to the elements, the school refuses to close during the five month rainy season in Zambia, when sporadic storms pour into classrooms and make teaching impossible.

The borehole in the compound ran dry months ago, leaving the school without water. There’s one dry latrine for the 119 boys and 111 girls who study here.

Don’t even own the school

To make matters worse, the community doesn’t even own the building. Even if the farmhouse and borehole could be renovated, its owned by another organisation and the school was supposed to move out in October.

Looking into the dark classroom

Many of the children leave home at five o’clock in the morning, and won’t be back for 11 hours. Some will do homework, most will help their families with chores or caring for livestock.

When they get here in the morning, the rooms are dark – they stay that way all day. There’s no power for electric lights, and reading is almost impossible. Children squeeze three or four around a desk made for one. Some stand for the whole lesson, others balance on metal framed chairs that are missing a leg.

Absenteeism here can be high, as students are often pulled out of school to work for their families, or are simply too weak from hunger to make the daily journey. The classes for grade one and grade two are often put together because there aren’t enough pupils to make a higher grade class possible.

With such basic facilities, it’s a wonder they both turning up at all.

But they do. And they love their lessons.

Sonia teaching the grade 1 & 2 pupils

Sonia Haloba Shanegubo teaches first and second grade students, and invites us to sit in on one of her classes. When she asks for a volunteer to come and count the number of apples she’s drawn on the blackboard, all 26 hands shoot into the air with a cry familiar to kids of every background.

“Teacher! Me!”

Sonia is proud of her proteges – especially the ones who’ve told her they want to be teachers when too when they grow up. She leads them in a special end of class song, Notuli Kumaanda, which the children dance to before leaving to play in the yard.

Sonia shows us their exercise books with pride, all have the right answers. She sighs as she picks one of them up.

“You see this one,” she says, “He writes his numbers on their sides still. This is because there were no trained teachers here until three years ago. The standards were very bad.”

A new, properly equipped classroom which Sonia’s class can make their permanent home will cost just £5,200 , a small part of the total for a new school. Please help.

-

Why classrooms are important

Richard Sikalunda, head man of Simikakata

Richard Sikalunda is a retired vet who lives in the 5,000 strong community of Simikakata. For the last seven years, he’s served as headman for the people here, their direct liaison with the district chief. Of all the things the community here needs, he knows that he has to focus on one project at a time to get things done.

In the future, he says, he’d like to build a clinic. The nearest town, Kalomo, is 7km away, and if there’s a medical emergency – like a difficult childbirth at night – the community doesn’t have the money to pay for the 25,000 Kwacha (approx £3) taxi ride to see a doctor. Right now, though, Sikalunda is standing in a site that he hopes, in six months time, will be a new school.

Relocating the current school from its current temporary base in a run down farmhouse is more important even than improving healthcare, he explains, because without reading, his community will never improve.

“When you have an educated community,” he says, “Most things can be done easily. Without learning, we cannot understand what to do.”

He talks about the rich agricultural potential of the land. Maize, soya and sunflowers are planted here between November and December. Most of the community are subsistence farmers, harvesting around 100 bags of maize per household. Some are capable of growing four or five times that amount, and are able to sell the surplus. Why the difference?

“We have people coming in to explain how to use agricultural machinery and fertilisers,” he answers, “But we cannot always remember the instructions. We don’t always know what to do. We cannot rely on interpreters all the time, and we don’t want to.”

-

If you can’t read, life is hard

Meeting the Simakakata community for the first time

Our NGO partner in Kalomo, Response Network, has helped us hit the ground almost faster than we can keep up. Within minutes of arriving in the town, we were taken to meet the local government representatives for the Department of Education.

Straight after leaving their office, we were taken to the community of Simakakata. It’s hard to believe that poverty like this still exists in the world, nor that it’s borne with such grace and warmth. Just a few kilometres from Kalomo, Simakakata is not so much a village, more a large geographical area of scrubland and cornfields peppered with tiny two or three hut clearings. It’s home to around 960 households, which is approximately 5,000 people.

At the moment, the school uses a dilapidated farmhouse as its temporary shelter. The building’s foundations are crumbling and few of the windows have glass. The nearest borehole is privately owned. Often, the community are turned away and forced to walk several kilometers to a source further away.

The children walk for up to 7km to start the school day at 7am. Its Headmaster, George Matantilo, is a government trained teacher, and has a staff of five, three of whom are volunteers from the local community.

In October, they were asked to leave as the building had been acquired another organisation. Fortunately, they have yet to take possession.

George’s school is exactly the kind of project LearnAsOne wants to support. He’s determined that any investment received from donors will be used to kickstart sustainable projects that the community can take on, own and maintain in the long run.

Volunteer Nerys gets a hand in the editing suite

In the last few months, the parents of his pupils have crafted 60,000 bricks to build their new schoolhouse. What they still need is materials for roofing, doors, foundations and cement, which they can’t manufacture themselves.

“Building is quicker now after the rainy season because we have food,” he says, pointing to the maize drying in the sun behind him. “Otherwise, everyone is too hungry.”

Why is a school important to a community who can’t even feed themselves the whole year round?

We asked one of the parents involved in the brick making project, Charles Sanjelele. He has lived here for 11 years, and has seven children between the ages of 17 and 4. They all attend classes at George’s schools. One day he hopes they’ll all leave the community and get jobs in the larger towns.

“To be educated is very important to us. If you can’t read,” he says, “Life is hard. It’s easier to get things done when you can read.”

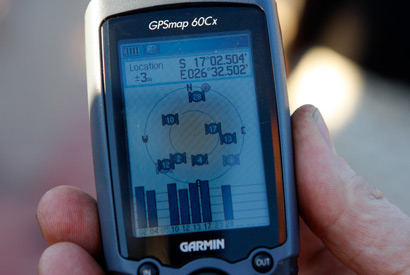

GPS co-ordinates at the centre of the village square

-

Decision time

So now comes the hard part. Deciding who to work with. I’ve seen 4 very different and interesting NGOs who are all doing amazing work to help children go to school in Zambia.

Trust is key

The LearnAsOne model is to work closely with a partner NGO to spend any money you are kind enough to give. This obviously needs to be done effectively and efficiently.

One of the key (and most expensive) needs of basic schools is construction: of classrooms, boreholes, sanitation blocks and teacher’s houses. Whilst talking with the 4 different NGOs I’ve asked for the costs to build a classroom block, all using the same official government plans. Rather alarmingly the costs have varied significantly with the most expensive being nearly 100% more than the cheapest.

Now in some cases the community are expected to provide skilled builders (as part of their contribution) and in others contractors are used. But even if these labour costs are excluded there is still a noticeable difference in price for no obvious reason. I’ve also been lucky enough to meet an ex-pat builder who is helping to fund a school close to where he lives and I’ve been able to compare his prices with the NGOs to give me a further benchmark. It’s safe to say we’ll be choosing one of the NGOs who are happy to offer costing transparency and prices we trust.

Community involvement and sustainability

All four NGOs I met were very keen to tell me about the community contribution to the project, which is fantastic to hear as schools only have a chance of success if communities want them in the first place. There is no better way to prove this than by volunteering time and material resources during the construction process.

In all cases the community is expected to provide free unskilled labour, plus locally sourced sand and stones which they make into bricks. A skilled builder is also required who must be approved by a Buildings Officer from the Ministry of Education. In some cases the community is expected to provide the the skilled labour and in others a contractor is used.

If a community is happy to provide a skilled builder themselves then this shows a total commitment to the project. It also saves a significant amount of cost.

Type of projects

As mentioned through out the blog post I’ve seen all sorts of schools this week. From town schools to rural schools. Basic schools to half built schools and High Schools. The need is great in all areas but we’ve decided that we would like to start by helping to tackle the Millennium Development Goal of providing free basic education to all children from grades 1-7.

We also want to work with a very basic community who are at the very beginning of their education journey. One key thing I’ve learnt this week is that there are two types of schools. Government and community. Trained teacher’s are supplied for free to government schools only. But it is possibly for a community school to become recognised by the government. It’s done on a case-by-case basis but some of the key criteria are that a basic classroom and a teacher’s house must be present. If we can help to get a community to this stage then there are very obvious benefits regarding the quality of teaching.

The updates

The final key part of the LearnAsOne concept is providing you with regular updates and stories from the community so you can meet some of the people who your donations are helping and see exactly what your money is being spent on.

It only makes sense for teams from LearnAsOne to visit Zambia a few times each year so part of this responsibility needs to fall on the NGO. There are two key criteria. Effectiveness of communication and the quality of updates.

Now it’s hard to make a judgement on the quality. All the NGOs showed me photographs from the field, of varying standards, and non really used a video camera. But this can be trained.

Effectiveness is much easier to see. I’ve been planning this trip for many months and the responsiveness of the NGOs to questions over email has varied enormously. One NGO has also been happy to text and voice chat on Skype making communication extremely simple and effective.

So the decision

I’ve avoided naming any names up until now. The good news is that one of the organisations ticks all the key boxes and I feel we also have a strong back-up should there be any problems or we want to expand in future.

The NGO we’ve decided to go with is Response Network.

They work with very communities who have very basic schools, are very easy to communicate with and their entire model is based around self-help and community empowerment. They are also the only organisation who insist on the community providing the skilled labour. I was initially sceptical about this, but I’ve learnt that the builder must be approved by the Ministry of Education before any work takes place. This approach shows a total commitment to the school by the community and maximises it’s chance of success.

So all that awaits now if for Adam, Brenda and Nerys to join me. Then on Monday morning we’ll be heading up to Kalomo to start documenting our first project live!

-

Day 5: ZOCS

On Friday with I met with ZOCS (Zambia Open Community Schools), the final NGO we have planned to meet on this trip. We discussed their work across Zambia and I was taken to visit Zambezi Sawmills Community School which is in Livingstone itself.

Charles Chama, the Program Officer for Community Development, travelled down from the ZOCS head office in Lusaka (about a 7 hour bus ride) for the meeting. And George Siankwa, Head of the Parent Community Schools Community (PCSC) for Sawmills, made a short journey across town.

We started with a long discussion about the scope of ZOCS work. They do numerous things in the education sector from working with communities to build schools, to teacher training, facilitating feeding programs and small micro-finance programs to make the schools more sustainable.

All of ZOCS work is with community schools which have been set up to help orphans and vulnerable children who are unable to pay for the uniforms and exam fees they need to go to government schools. Without ZOCS intervention many children miss out an education altogether.

They are affiliated with 24 community schools in the Livingstone area, plus 121 others in the Southern region. In order to become affiliated a school must have been in existence for 3/4 years and have registered with the Ministry of Education. They are then eligible for support, but there is only enough funding to support a small number of them.

One very interesting area that ZOCS is involved in is teacher training for the volunteer teachers in the community schools. Government schools provide trained teachers, but in community schools the teachers are usually volunteers so this is a key part of the ZOCS program. They use the same facilities and teaching materials as the government teachers, but classes are carried out at weekends and during school holidays. It’s a great idea, and something I’ve asked for more information about.

Zambezi Sawmills Community School along with some sand collected by the community to build bricks for a new classroom.

Following our discussions I was taken to visit the Zambezi Sawmills school which ZOCS suggested as a first project. It’s just 3kms from the centre of Livingstone and very much a town school. There are three classrooms and a sanitation block based on a small plot of open land which is surrounded by houses. 200 children attend the school in three shifts throughout the day. Grades 1-7 are catered for.

The key needs are a fence to provide the children with security, a second 1 x 3 classroom block, tables and chairs for teachers plus teaching and learning materials.

It’s another very different project to consider. It’s not in a rural area, but it does help some of the most vulnerable children in the community. ZOCS have relationships with multiple schools in the southern region, but their main offices and majority of their work is currently based in and around Lusaka.

So all that now remains is to work out which NGO we want to start working with. I’ve been discussing this with the trustees throughout the week and we are ready to make a decision. I’ll update you all in the next blog post.

-

Meet the team. Brenda Veldtman, Volunteer Photographer

The volunteer team is completed by our amazing photographer Brenda. You can see her work here.

Name:

Brenda Veldtman

Occupation:

Freelance Photojournalist

Who are you?

I am a freelance photojournalist from South Africa. My passion is to tell stories through pictures. The first 6 years of my career I worked full time as a press photographer for two of the leading Afrikaans Newspapers in South Africa. I am freelancing now and specialise in documentaries.

What will you be doing in Zambia?

I will be documenting the lives of the people and children in Zambia in need and tell their stories as truthfully and honestly as possible, hopefully touching other people’s hearts so that they can donate to LearnAsOne!

Why are you going on the trip?

I want to contribute to this wonderful cause.

Have you ever done anything like this before?

Yes - I have worked with other NGO’s before in Africa, but this is exciting as we will be reporting back in real time.

Any big concerns about the trip?

Africa is unpredictable and you never know what to expect.

What luxury item are you going to pack?

None, my camera equipment will take up all the space…

What will you miss most?

My husband, cat and dog.

If you have any questions for Brenda please leave them in the comments section below.

-

Meet the team: Nerys Evans, Volunteer TV Producer

Our team of volunteers will be joining Steve in Livingstone on Sunday. As they finalise their travel arrangements, what better way to pass the time then introduce video guru Nerys, who’ll be capturing the community we visit on film.

Name

Nerys Evans

Occupation

Video Director / Producer

Who are you?

I’m a full time Video Director / Producer in leading new media firm Tinopolis Interactive. My previous history is in documentary and factual productions, covering social issues, wildlife, art and history for BBC, ITV and Channel 4 Wales.

What will you be doing in Zambia?

Producing and filming videos for the LearnAsOne website and documenting our trip for a Welsh magazine programme.

Why are you going on the trip?

It has been a life long ambition to apply my experience to aid people who do not have access to mass communication. Documentaries are perfect storytellers in the right commissioning hands or charitable organisations.

Have you ever done anything like this before?

I’ve done wildlife, history, social and art productions and I’ve been to developing countries but this is the first time for me to combine both.

Any big concerns about the trip?

Snakes and spiders. We generally don’t get on.

What luxury item are you going to pack?

iPod.

What will you miss most?

My friends and family but I know they’ll be there when I get back. I intend on making the most of my time in Zambia.

If you have any questions for Nerys please leave them in the comments section below.

-

Day 4: Butterfly Tree: Mukuni Village

Yesterday I visited the third NGO, the Butterfly Tree, which is a small organisation with registered offices in both Zambia and the UK. I was invited to visit Mukuni Village by Jane Kaye-Bailey, who founded the organisation, to see the work that has already taken place and also hear from the community what they still need.

Mukuni Village is one of the largest villages in Zambia with a population of around 7,000. It’s just 7kms from Victoria Falls and is a popular destination for tourists day trips. The Village is part of the Mukuni Chiefdom (think district in the UK) which has a total of 12 schools for around 15,000 people. A High School is currently being built in the Village, but some of the surrounding villages have far more basic facilities with just three or four classrooms for grades 1-7 (primary school).

I met with Martin and Mupotola who showed me some of the classrooms, pit latrines and teacher’s houses in the Village itself. They follow standard plans drawn up by the government so any structures built in the satellite schools would be almost identical.

A recently built classroom block in Mukuni Village

I was then taken through the accounts, cash book and a full breakdown of costs for the latest building to have been constructed. The level of transparency was very impressive and I didn’t even have to ask to see it, they wanted to show me. Mupotola also connected a laptop up to the Internet via a USB dongle and it was easy to send a tweet and an email so communication would be no problem at all.

The schools in Mukuni are currently on holiday (they start again on Monday) so I didn’t get to meet any of the children, but I didn’t really need to. I was told the greatest need is at Siamasimbi school which is about 30kms from the Village and has just three classrooms for seven grades.

So that’s another day run, and another good project seen. I was particularly impressed with the level of transparency which is what the LearnAsOne idea is all about. It leaves me with one more NGO to see and then a hard decision to make.

How will the decision be made?

Now that I find myself in the fortunate position of having met three good NGOs it comes down to a few factors. Who is the most transparent? Who is easiest to communicate with? Who has the most experience? What scale can we achieve with a single NGO if our fundraising is successful. And what type of schools do we initially want to work with? Very basic, partly built, or High School.

I’m continually mulling all of this over with the trustees and a decision will be made tomorrow night or on Saturday. The volunteer documenting team is due to join me on Sunday and we’ll all travel to the first project on the Monday.

-

Day 3: FAWEZA and Musukotwane Basic School

There was a total power and Internet failure last night so I apologise that this update is a little late.

On Wednesday I met with FEWEZA (Forum for African Women Educationalists of Zambia), the second of four potential NGO partners I plan to meet this week.

They have been working in Zambia since 1996 and have programs all across the country including 58 interventions in the Southern region. This covers everything from scholarships, to reading clubs, safe houses for girls and working with communities and the government to build schools.

Musukotwane Basic School in Kazangula Province, about 50kms north of Livingstone.

I was taken to visit Musukotwane Basic, a government school which has 8 classrooms for 452 pupils (56 pupils per class). I was told that most of these classrooms leak during the rainy season and around two-thirds of pupils don’t have a desk.

One double classroom block even has a bee infestation which the community are unable to get rid of. There is approximately 1 text book per 10 pupils. The school does have 16 government funded teachers, but only 6 teacher’s houses for them to live in.

In one classroom we were met by an angry swarm of bees

Despite this Musukotwane is one of the most advanced schools in the area teaching all the way through to grade 9 (primary education is up to grade 7). This means some children are forced to travel from up to 18kms away if they want to continue their studies so there is a great need for boarding facilities.

I learnt all this whilst being shown around the school by the head teacher Mr Dominic M. Sumusuka. He was also very keen to highlight that there is no High School within 100kms of Musukotwane so if pupils want to enter grades 10, 11 or 12 their only options is to travel and become a boarder far away from home. That’s assuming their parents can afford the school fees. There are currently 68 pupils waiting to enter grade 10 in the area.

Some of the children at the community meeting

To conclude the brief visit a community meeting was called to explain why we were there: primarily to get an understanding of what FEWEZA does and to listen to the needs of the community they recommended to us. This was very clearly explained to all parties from the outset and no guarantee of funding was made.

It also gave the community the chance to ask questions and for some of the parents, teachers and the pupils to explain the the greatest needs as they saw it. Classrooms for grades 10-12 plus boarding facilities was the unanimous answer.

So where does this leave us?

The first thing we need to do is pick an NGO who we can trust. FEWEZA come highly recommended, partner with some major donors like USAID, UNICEF and World Vision, plus they have a very strong relationship with the Ministry of Education.

In terms of the project the needs in the community are vast, especially for a High School, so that children no longer have to travel over 100kms to continue their education. But we can only start with one project and we need to weigh this up against the need for basic schools in communities who are at the very start of their education journey: the kind of project we had in mind before traveling to Zambia.

There is a clear need for both and this is was backed up by a meeting with representatives from the Ministry of Education at the end of the day. It’s something I need a little time to mull over with the trustees, but it’s great that there are now two strong options for partnerships and there are still two more NGOs to meet!